http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-32066222

Anyone who wants to understand Vladimir Putin today needs to know the story of what happened to him on a dramatic night in East Germany a quarter of a century ago.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/04/putin-gay-biography_n_4385360.html

Friday, March 27, 2015

Monday, March 23, 2015

Sunday, March 15, 2015

Putler ~ Magician, Mouse or Monster (2006) Ed Lucas

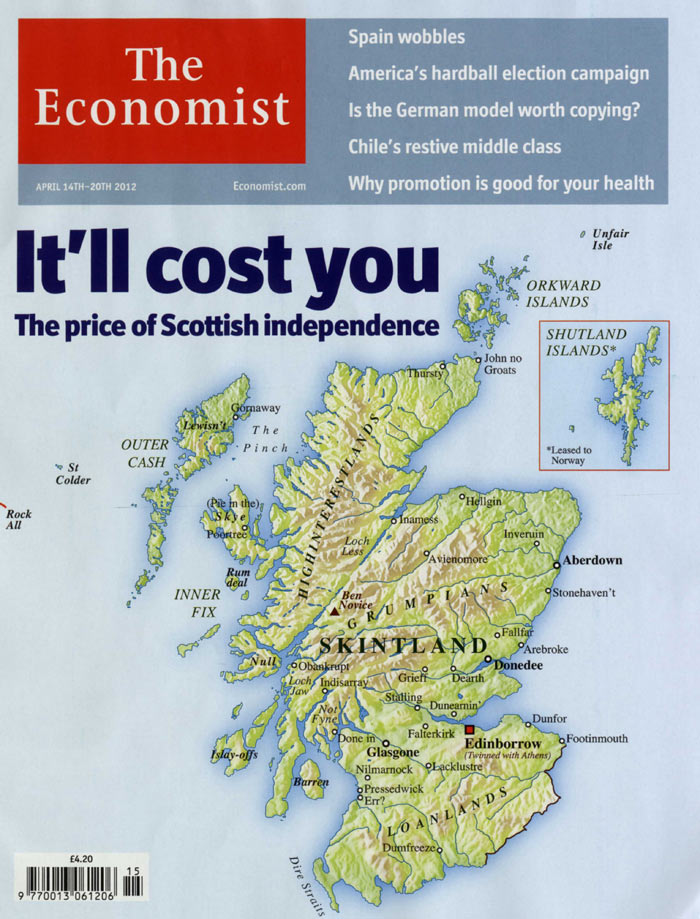

This ... long piece on Putin was not written for the Economist and is likely to stay unpublished. I am posting it here for people with a detailed interest in Russia. Comments are welcome, but I should stress that I am not the Economist's Moscow correspondent and this is not an official Economist article in any way shape or form.

Vladimir Putin. Magician, Mouse or Monster

I saw a lot of President Vladimir Putin when he became my neighbour. At least I saw him most days; I doubt he saw me, fuming at the side of the road as his presidential convoy swept past at 80mph all the way to the Kremlin from his newly built presidential palace in our village of Kalchuga, 10 miles outside Moscow.

Mr Putin's country pad and its effect on our village highlighted for me his regime's authoritarian, bullying style. The past week's rows over gas have now brought that home for the rest of the world. Russia is not just aggressive towards its neighbours, but contemptuous of world opinion. Under Mr Putin, it is no longer a basket case: it is rich, powerful, unpredictable and malicious.

The first thing I noticed about my neighbour was that he had to build a new house: he hadn't inherited the sumptuous country retreat of his predecessor, Boris Yeltsin. That was because the deal between Russia's crooks and spooks that brought Mr Putin, then an unknown and undistinguished bureaucrat, to power in 2000 included an iron-clad agreement that the outgoing Yeltsin clan would not just be immune from prosecution, but also keep the spoils of officecash, cars and country cottages.

Secondly, the Putin "dacha" or "cottage" (it was about the size of Sandringham) was built at amazing speed and great secrecy on a disused airfield at the edge of our village. That infuriated my sons, who were learning to ride bicycles there. It also illustrated an important point about the way the Russian state works. It may be corrupt, lethargic, and stunningly incompetent in general. But when the man at the top wants something done, it happens fast and ruthlessly.

Our Russian neighbours in the village were unhappy at the rush of development that followed Mr Putin's arrival. One new rich neighbour with close Kremlin connections concreted over the village green to make a driveway for his mansion, beating up an elderly neighbour who objected. Then a property company, also with Kremlin links started bulldozing a nearby forest for a housing development. That taught us two lessons about Mr Putin's Russia. It was startlingly encouraging to see the effects of ten years of democracy: the villagers reacted not with traditional Russian apathy, but with lawsuits, petitions, and when all else failed, direct action: they blocked Mr Putin's road to work. The sad lesson was that the legal system brushed them aside; that their petitions were ignored, and that their modest demonstration met with a tough Soviet-style response from the authorities. The developers and their mates in officialdom offered cash andbizarrely and for reasons I never understoodfridges to those locals willing to join a rival outfit set up to campaign for the new housing development and denounce the protestors as anarchists, greens and communists. Setting up fake front organisations was a classic Soviet-era tactic. So was bullying opponents. The villagers received blunt threats: "we will turn up with a bit of paper saying your house is built on our land, and then we will bulldoze it" a shadowy official told my next-door neighbour.

Such are the paradoxes of Putin's Russia. There is prosperity amid lawlessness. The outward trappings of democracy decorate an increasingly authoritarian system. Imperial pomp and ceremony surround a modest-seeming man from a humble background. But the biggest puzzle is that what the all-powerful Mr Putin really wants, believes and can do is still a mystery to Russians, as it is to the former captive nations of eastern Europe, and to the rest of the world. Sometimes it seems a mystery to Mr Putin too. Certainly when he was first nominated by Mr Yeltsin as designated successor, he seemed as baffled as everyone else. "I am obeying orders," he told journalists wryly in the summer of 1999 when he first emerged, blinking and tongue-tied, into the world's view. Mr Yeltsin, the bearlike destroyer of Soviet communism, was by then so confused and erratic in his rule that few people thought his choice of successor would mean much. Mr Putin, a dull, publicity-shy bureaucrat with not an ounce of charisma, and the fifth prime minister in 18 months, would surely be swept aside by some bouncier character, such as the rumbustious wheeler-dealer mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov. Yet the provincial Mr Putin, a second-rate spy turned local-government official, moved seamlessly into the top job, and now presides over the world's largest country, over its second-biggest nuclear arsenal, and over its most strategically important gas reserves.

To everyone's surprise, he rapidly became very popular. For the public, he was sober, young and athleticeverything that Mr Yeltsin wasn't. And for the Russian elite, he was the ideal compromise.

The spooks, longing to restore Russia's great-power status, liked him because of his intelligence background: not quite the top drawer, perhaps, but certainly part of the charmed circle that had studied at the Red Banner Institute, the top Soviet spy-school.

And he was palatable for the crooks. These were the sharpwitted shysters who had run black-market businesses during the late Soviet era, and had gone on to grab amazingly lucrative stakes in the free-for-all that followed over who would control Russia's natural wealth, and exploit the huge opportunities that capitalism created in banking, transport and property. Having served as a trusted official in the Kremlin, Mr Putin knew the way that wealth and power in Russia overlapped. Mr Yeltsin's highly influential daughter, Tatyana Dyachenko, and her husband Valentin Yumashev, the two figures in the Kremlin that epitomised the reckless greed of 1990s Russia in their blurred roles as high officials and highly successful businesspeople, were solidly behind the new man.

So at the beginning, many people hoped that Mr Putin would be a magician-president who would kick-start reforms and drag Russia into the modern world. Even democratic-minded Russians who loathed the KGB and everything it stood for wanted to give the new man a chance. And for a time it looked good: he cracked down on the "oligarchs"the arrogant, lawless tycoons who had looted Russia in the 1990s. True, that meant closing down their once-flourishing media empires, all of which are now run by tame businessmen close to the Kremlin. But that seemed defensible. Independent television is one thing; pocket stations that blatantly serve the commercial interests of their owners are hardly an ornament to democracy. Mr Putin might have a steely manner, but he spoke nice words. He praised democracy and civil society.

Many outsiders were prepared to give Mr Putin the benefit of the doubt too. George Bush said that he had looked into the Russian president's eyes and "seen his soul". Tony Blair enjoyed lavish nights at the opera during visits to Russia. Gerhard Schroeder got on so well with the German-speaking Putins that they spent a family Christmas together; Mr Putin intervened personally to help Mr Schroeder bend the rules and adopt a Russian orphan.

The first doubts appeared over Mr Putin's effectiveness. It was increasingly clear that he wasn't a magician: The growth in the Russian economy owed everything to high prices for oil and gas, and almost nothing to the half-hearted, half-baked reforms coming out of the Kremlin. Many began to think Russian president was a mouse, an over-promoted minor spook who spent his days obsessively reading intelligence reports, but was ignorant of the big picture, and lacking the drive and vision needed to run a country as huge and troubled as Russia. Mr Putin might be good at appearing on television, in elaborately choreographed stuntsflying a fighter plane, whizzing down ski slopes, hurling opponents across a judo mat. He certainly seemed to enjoy themwhat a contrast to his humble origins as a scrawny, bullied youngster from a hard-up family living in a rundown communal apartment in Soviet Leningrad. But many felt that real power surely lay elsewhere, with the sleazy, wily old-timers inherited from the Yeltsin era.

Certainly Mr Putin's public utterances, or the lack of them, were often mystifying in their quality and quantity. At times of crisis, such as terrorist attacks by Chechen rebelsthe direct result, many say, of his regime's brutal policy of reprisals in that breakaway republiche simply vanishes from public view. When he does speak in public, his remarks have seemed at times astonishingly callous and ill-judged. Asked on live television about the Kursk tragedy, in which 118 Russian submariners perished, Mr Putin shrugged and smirked: "it sank". Speaking about Chechen rebels, he resorted to slang normally heard only in the mouths of gangsters, which could be loosely translated as "if we find them in the shit-house, we'll whack'em in the shit-house". Criticised at a press conference in Brussels for his harsh policies in Chechnya, he suggested that the offending journalist should undergo ritual castration at the hands of Muslim extremists. At a joint press conference with Mr Blair, he could not resist the temptation to humiliate the British Prime Minister about the absence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. "Maybe they're here, under this desk" he sneered. Mr Blair has never trusted him again.

What is really scary about Mr Putin is that despite his undistinguished record in office, his limited intellectual and cultural horizons, and his bullying manner, he has still been able to turn the tables on the people who put him in power. Russia may still be shambolic, but it is a shambles over which he and his team of Kremlin loyalists, mostly from the old KGB, is in undisputed charge. Everyone who has dared challenge or resist Mr Putin's rule has been sidelined, neutralised or humiliated. The Yeltsin advisers are gone. The tycoons are in jail, in exile, or in political purdah. The media is cowed. The opposition parties are shams, run to give the appearance of pluralism to the Russian public and the outside world, but with no chance of taking real power. The once-mighty regional chieftains like Mintimir Shaimiyev of Tatarstan and Yuri Luzhkov of Moscow, who used to run Russias's cities and regions as private fiefs are now, like the central government itself, merely nervous servants who carry out the presidential administration's commands as their predecessors once obeyed the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

That is thanks to the way the Russian state works. There is huge power for the man at the top, regardless of whether he is impressive or not. Lenin, Brezhnev, Andropov and Yeltsin all ruled for years as sick men. Mr Putin is the first Russian leader since Peter the Great to have the simple advantages of being punctual, efficient, fit, sober and concise.

Mr Putin's KGB background adds both useful skills, and an aura of intimidating mystery. Even Russians who hated and feared the Soviet secret police have grudging respect for it. It was an organisation that recruited the brightest and toughest people in the country, and gave them excellent training. All KGB officers are trained in target acquisition: gaining a target's cooperation through bribes, flattery or threatsand then bending them to your will. Some joke that Mr Putin's relationship with Mr Schroder is a public example of this.

Privately, Mr Putin seems to enjoy showing off the fruits of his spy networks and their dungeons packed with information. A western newspaper editor who met him was amazed when the Russian leader murmured at the start of the interview, in English, "I hope your wife's mother recovers soon." Not even the editor's closest colleagues knew that his mother-in-law was gravely ill.

Mr Putin also understands the way that corruption both fuels Russia and makes it manageable. When the rules are impossible to observe, everyone is vulnerable. It requires only a phone call from the top and the tax police, special anti-corruption police, anti-racketeering squad and all manner of other menacing, implacable monsters descend on an uncooperative individual, company and organisations. Even the honest cannot hope to escape the government inspectors: they will always find something. Such arbitrary rule is inefficientbut Russia's oil and gas wealth makes it affordable.

In short: Mr Putin is neither a magician, nor a mouse. But he increasingly looks like a monster. He has unleashed the two most sinister forces of the Soviet past: the totalitarian habits of the security services, and the imperialist urge that lies deep in the Russian psyche. Put politely, he wants the Russian state to be strong at home and abroad. Put crudely, he is trying to recreate an empire reminiscent of the Soviet Union: feared by its own people and its neighbours in equal measure.

The big question now for Russia and the world is what happens next. The bullying of the former captive nations seems set to continue: the latest spat about gas has illustrated that rich Europe is unwilling or unable to protect the east European countries that are captives of the Russian gas monopoly. The slide away from democracy is continuing too. Here 2008 will be decisive, when, according to the Russian constitution, Mr Putin should step down as his second term in office ends. Few believe that he, like his predecessor Boris Yeltsin, will step gracefully away from power in return for immunity against prosecution for him and his family. Some smart money bets that he will leave a puppet figure in the Kremlin, and move over to Gazprom, the hugely powerful Russian gas monopoly. Others think he will change the constitution. Or he may create a new country, a union of Russia and Belarus, and become president of that.

But one thing is clear and scary. The world may still know very little about the prickly little ex-spy who now runs Russia. But it is going to be hearing about him for a long time to come.

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Britain may broadcast Putin's financial secrets to Russian people

The EU has applied asset freezes and visa bans to 151 Russian and Ukrainian people and 37 companies regarded as complicit in the seizure of Crimea and the invasion of east Ukraine.

The wealth of Putin’s court is opaque, but undoubtedly runs into tens of billions of dollars held in offshore accounts and property in London and New York. Many of his closest associates made their fortunes during the chaotic mass privatisations of state assets during the 1990s. Official statements of Putin’s wealth - a £96,000 a year salary, a flat and three cars - are frequently met with derision.

Mr Cameron has suggested the BBC budget should be increased to help its Russian and Ukrainian language services counter Russian television propaganda.

Putin's money men

The wealth of Putin's inner circle runs to tens of billions of pounds.

Vladimir Yakunin

Vladimir Yakunin

Head of Russian Railways, the country's biggest employer, since 2005. He has been part of Putin's St Petersburg circle since the 1990s, and is dogged by claims from opposition activists over his wealth. He accompanies Mr Putin on overseas visit, and was in charge of construction during the Sochi Winter Olympics. He has been hit with US sanctions. His network is unknown but his official salary is $15 million.

Gennady Timchenko

Gennady Timchenko and wife Elena

Founder of Gunvor, the Swiss-based oil trader, he sold his stake just before being hit by US sanctions. His net worth is reckoned to be $14.5 billion, according to Forbes. Putin is said by the US to have "investments in Gunvor and may have access to Gunvor funds". The company strongly denies that claim, and has not been subject to foreign sanctions.

Yuri Kovalchuk

Yuri Kovalchuk

Once dubbed one of Putin's "cashiers". He is the largest shareholder of Bank Rossiya, called by the US the "personal bank for senior officials" of Russia. He is a member of the Ozero Dacha, a community of lakeside homes of Putin and his allies. His wealth is estimated to be $1.4 billion. He is hit by US and EU sanctions.

Arkady and Boris Rotenburg

Arkady is Putin's old judo partner, and is subject to EU sanctions.. The brothers have interests in pipelines, road construction and banking, and are presidents of Dinamo Moscow hockey and football clubs respectively. They received billions of dollars of contracts for the Sochi games. Their personal wealth is said to be $2.5 billion.

Igor Sechin

Igor Sechin

President of Rosneft, the state oil company, and the former deputy prime minister. His salary was $50 million last year. He is one of the most powerful figures in the administration, and is said to "economic interests" with Putin.

Infowars

Tweets issued by the British embassy in Ukraine highlight how heavy weaponry used by separatists in the east of the country are Russian-supplied - and have highlighted the impact of sanctions on the Russian economy

Monday, March 9, 2015

Murder of a friend ~ Edward Lucas

Murder of a friend

My immediate reaction to the opposition leader’s death on Friday evening was misery and fury. Now, it is fear. Fear for what the assassination of my friend may herald—either a return to a terrifying past, or a descent into a still more alarming future.

Edward Lucas

Boris Nemtsov was my closest friend in Russian politics. I had known him since the late 1990s when he was trying vainly to stem the sleaze and authoritarianism that eventually brought Putin and his ex-KGB cronies to power.

Unlike some Russian liberals, Nemtsov saw through Putin from the beginning. He disliked the new leader’s background as an unrepentant KGB officer, and worried about his murky years spent in the city administration of gangster-ridden St Petersburg.

He decried the political bargain that the new regime offered as sinister and misleading: Russians craved stability but it should not come at the price of ending political pluralism.

As the regime tightened its grip on the electoral system, Nemtsov and other liberals were excluded from public life. He turned to protests and to investigating corruption and incompetence.

One set of possibilities surrounds the theory that his assassination was ordered by the Putin regime. It could be a simple attempt to silence him. Nemtsov was about to release a report on Russia’s war in Ukraine. I doubt that would justify his murder. His other investigative reports were damning—but they had little impact, because the official media ignored them. Russia’s role in attacking and destabilising Ukraine is well proven. The shortage is not of more evidence, but of will power in the West. Even Nemtsov could not provide that.

Nor do I think it likely that he was killed to forestall a protest march planned for last Sunday. The opposition in Russia is barely worthy of the name: Nemtsov himself told the FT shortly before his death that he was now a mere dissident. The regime has plenty of way of keeping its quarrelsome and marginal critics in check, chiefly by harassing them through the criminal justice system. Why add the extra complication of murder?

More likely is that the killing was symbolic. The official media, with suspicious unanimity, is taking the line that Nemtsov was murdered by other opposition elements, or possibly their foreign paymasters, in order to destabilise Russia.

It is hard to follow this perverse reasoning, or to find any facts to support it. But as with the Kirov murder in 1934, which gave Stalin reason to purge Soviet life of any dissent, Nemtsov’s killing could give the regime grounds for launching a serious crackdown.

Russia’s history is drenched in blood and tears. Countless people died in the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s. The pretext for these purges was a spectacular murder. The bon vivant Sergei Kirov, Communist Party boss in Leningrad, was a growing threat to the brutal, suspicious Josef Stalin.

Though a die-hard communist, he thought the country’s leadership had gone too far. Kirov objected to the persecution of the Soviet peasantry which had led to lethal famines in Ukraine and elsewhere. And he resisted Stalin’s manic, paranoid tightening of Communist Party discipline.

That cost him his life. In a mysterious shooting on December 1st 1934—amid astonishing negligence by his bodyguards, in a prestigious party headquarters building, the Smolny Institute—Kirov was shot dead.

Stalin responded with a vehement public condemnation. He carried the coffin at Kirov’s funeral and took personal charge of the investigation. But it mushroomed into a massive purge of the Party—and then the whole country. Hysterical suspicions, of treason, terrorism, sabotage, and espionage, swirled through every corner of Soviet life.

Yet even similar motives as with the Kirov murder seem a bit unlikely. True, the Kremlin likes phoney legalism to mask its repression at home and aggression abroad. But why go to the trouble of killing Nemtsov, when so many other pretexts abound?

Most likely is that Nemtsov’s killing was a political signal from one part of Russian politics to another: that it is now acceptable to kill a former deputy prime minister within a stone’s throw of the Kremlin. The fact that the murder happened on the newly proclaimed Special Forces Day may have something to do with it.

In the Kremlin’s propaganda the Russian opposition, along with Zionists, Fascists, paedophiles and CIA plots are stitched together into fiendish plots against holy Mother Russia. Some senior Russians know privately that it is nonsense. After all, they educate their children in this demonic West, and invest their money there. But others believe it.

Boris Nemtsov—brilliant, charming, handsome, honest and brave—was no Kirov. He was no blood-stained Communist apparatchik, but a physicist who turned to politics out of patriotism. Nemtsov was a pro-Western Jewish liberal who bravely decried Russia’s war in Ukraine as an outrage, was a particular hate figure among these people. Many would like to kill him anyway—especially if it would also signal to the Kremlin that if the regime does not get tough with traitors, others will.

The official reaction to Nemtsov’s murder has the most sinister overtones of the past. The Russian president Vladimir Putin has taken personal charge of the investigation of his opponent’s death.That is offensive as it is farcical. The many murders and beatings of Kremlin critics in recent years have gone unsolved, amid bluster, confusion and incompetence.

The authorities show no sign of treating this case any differently. The investigators detained Mr Nemtsov’s girlfriend, a Ukrainian model, and have ransacked his apartment, seizing his computers and papers.

But the truly chilling echo of the Kirov case comes in the media coverage. Russia has already descended into a propaganda hell in which the Russian opposition, along with Zionists, Fascists, paedophiles and CIA plots are stitched together into fiendish plots against holy Mother Russia.

That is all too reminiscent of the Stalinist media in the 1930s. Dissent is treason. Contact with foreigners is espionage. Enemies are everywhere.

As Karen Dawisha, a brave American academic who has laid bare the links between the Putin regime and gangsterdom, has written, “when the Kremlin publicly labels the opposition leaders as enemies, and spews out nothing but hatred toward those who have a right to demand freedom, then killings – irrespective of who pulled the trigger—are a logical result.”

Now—in a truly sinister twist reminiscent of the Kirov case—official media is blaming Nemtsov’s allies in the opposition for his murder. In the Kremlin’s perverse logic, they are the likely culprits, because they will benefit from the outrage around the killing.

In truth, that outrage is limited. A demonstration yesterday attracted tens of thousands of mourners—a respectable total, but not nearly enough to rock the regime. The shooting instils fear, rather than stoking indignation.

Many critics of the regime, in Russia and abroad, are asking who will be next.

My friend Yevgenia Albats, editor of one of the few remaining independent magazines in Moscow, says: “the hunting season is open.”

The logic may be bizarre, but there is no doubting the Putin regime’s determination to stay in power.

If, as the regime seems to be arguing, the Nemtsov killing was an attempt by the opposition and its foreign paymasters to destabilise Russia, then the response must be ruthless. Lies and terror will have Russia in their grip.

It may be hard to imagine anything more unpleasant than the crooked spooks of the Putin inner circle. But the climate they have created is fostering even more loathsome elements.

They include the fearsome legions of the despotic Ramzan Kadyrov, the eccentric strongman leader of Chechnya. Having lost a war of secession against Moscow, the warlike Chechens have now thrown in their lot with Putin—and have gained increasing and sinister influence in Russian politics as a result.

Of similar vein are the separatist insurgents in eastern Ukraine. Thuggish paramilitaries, often with ties to organised crime, they are like the hard men of the Troubles generation in Northern Ireland. Like the IRA and UDA they have a taste for violence, coupled with intransigent, extremist political views.

In the case of the new Russian hardliners, these are a toxic cocktail of Stalinist nostalgia, overt fascism, ultra-orthodox religiosity and a bitter hatred of the West. Some are also part of motorcycle gangs with exotic names such as the Night Wolves.

These people do not see Mr Putin as a sinister tyrant. They think he is too soft.

They would have no compunction in murdering someone like Nemtsov—and might see it as a way of signalling to the Kremlin that if the regime does not get tough with traitors, others will.

I hope we in the West are ready for an era in Russia which may make the last 15 years seem like little more than mild inconvenience.

Edward Lucas is the author of The New Cold War: Putin’s Threat to Russia and the West, and Deception: Spies, Lies and How Russia Dupes the West

Friday, March 6, 2015

The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money

http://www.interpretermag.com/the-menace-of-unreality-how-the-kremlin-weaponizes-information-culture-and-money/

"In recent years, the Kremlin has made much use of information warfare, gaining support in the West from nostalgic communist fellow travelers, the rising far-right and conspiracy theorists. The rebranding today of the international branches of Russia’s state-owned Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today) news group as Sputnik International speaks of the Kremlin’s intent to influence and manipulate opinion abroad. Russian state-owned or state-controlled media also serve to distribute disinformation, including outright lies, as best exemplified by fabricated reports of the crucifixion of a child by Ukrainian forces"

Wednesday, March 4, 2015

Sign the Petition Please

https://secure.avaaz.org/en/petition/CSR_Department_directors_at_Western_companies_based_in_Moscow_Move_to_Kiev/?aRaFgjb

Люди Украины умирают за права и свободу, которые мы принимаем как должное. Хотя никто и не ожидает, что BP, Nestle и другие транснациональные корпорации откажутся от их отношений с Россией, бойкотируйте их, пока они не перевели их региональные штаб-квартиры в Киев. Как минимум это подаст сигнал Путину и его клептократам, что у Запада есть совесть. Действуйте сейчас и передайте это сообщение дальше

Ukrainians are dying for the rights & freedom we take for granted. Nobody expects BP, Nestle, P&G & other multinationals to give up their business with Russia. Boycott them until they move their regional HQs to Kyiv; as a minimum they should shift their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) departments. This sends a signal to Putin & his kleptocrats that the West does have a conscience. Act now and pass this message on

Ukraińcy umierają za wolność i prawa obywatelskie, którymi my możemy cieszyć się bez wysiłku.Noe oczekujemy, że międzynarodowe koncerny, takie jak BP, Nestle, Procter & Gamble i inne, przestaną robić interesy w Rosji. Będziemy jednak bojkotować je aż do chwili, gdy nie przeniosą swoich regionalnych siedzib z Moskwy do Kijowa. Jako minimum i pierwszy krok oczekujemy przeniesienia departamentów CSR. Wyślijmy sygnał Putinowi i jego kleptokracji, że Zachód ma sumienie. Przyłącz się do nas i prześlij tę informację do znajomych.

Chaque jour les Ukrainiens meurent pour leurs droits et libertés qu'ils conciderent comme acquis . Bien que personne ne s'attend à ce que British Petroleum, Nestlé et les autres multinationales coupent leurs relations avec la Russie, boycottez -les jusqu'à ce qu'ils transférent leur siège régional à Kyiv, la capitale ukrainienne. Au minimum, cela montrera à Poutine et à ses bureaucrates-cleptomanes que l'Occident a une conscience. S'il vous plaît, agissez maintenant et transmettez ce message

Українці гинуть за права та свободу, які ми сприймаємо як належне. Хоча ніхто не очікує, що BP, Nestle та інші транснаціональні корпорації відмовляться від своїх відносин із Росією, бойкотуйте їх доки вони не переведуть свої регіональні штаб-квартири до Києва. Як мінімум, це надасть сигнал Путіну та його клептократам, що у Західа є совість. Дійте зараз та передайте це повідомлення далі

Menschen in der Ukraine sterben für die Rechte und die Freiheit, die wir für selbstverständlich halten. Obwohl niemand erwartet, dass BP, Nestle, P&G und andere multinationale Unternehmen sich weigern, von Ihren Beziehungen zu Russland, boykottíeren Sie die, bis Sie die regionale Zentrale nach Kiew verlegen. Zumindest es wird ein Signal sein an Putin und seine Kleptokraten, dass der Westen hat ein Gewissen. Handeln Sie jetzt und senden Sie diese Nachricht weiter

Gente di Ucraina muore per la sua indipendenza e liberta, questo è normale.Nessuno aspetta che BP, Nestle ed altri multinazionali smettono qualsiasi relazione con la Russia , baicotate loro, prima ,che ci trasferiscono le loro ufficci a Kiev.come il minimo,questo fara da segnale a Putin e suoi che l'ocidente a la coscienza pulita. Dovete aggire subito condividete questo messaggio

Люди Украины умирают за права и свободу, которые мы принимаем как должное. Хотя никто и не ожидает, что BP, Nestle и другие транснациональные корпорации откажутся от их отношений с Россией, бойкотируйте их, пока они не перевели их региональные штаб-квартиры в Киев. Как минимум это подаст сигнал Путину и его клептократам, что у Запада есть совесть. Действуйте сейчас и передайте это сообщение дальше

Ukrainians are dying for the rights & freedom we take for granted. Nobody expects BP, Nestle, P&G & other multinationals to give up their business with Russia. Boycott them until they move their regional HQs to Kyiv; as a minimum they should shift their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) departments. This sends a signal to Putin & his kleptocrats that the West does have a conscience. Act now and pass this message on

Ukraińcy umierają za wolność i prawa obywatelskie, którymi my możemy cieszyć się bez wysiłku.Noe oczekujemy, że międzynarodowe koncerny, takie jak BP, Nestle, Procter & Gamble i inne, przestaną robić interesy w Rosji. Będziemy jednak bojkotować je aż do chwili, gdy nie przeniosą swoich regionalnych siedzib z Moskwy do Kijowa. Jako minimum i pierwszy krok oczekujemy przeniesienia departamentów CSR. Wyślijmy sygnał Putinowi i jego kleptokracji, że Zachód ma sumienie. Przyłącz się do nas i prześlij tę informację do znajomych.

Chaque jour les Ukrainiens meurent pour leurs droits et libertés qu'ils conciderent comme acquis . Bien que personne ne s'attend à ce que British Petroleum, Nestlé et les autres multinationales coupent leurs relations avec la Russie, boycottez -les jusqu'à ce qu'ils transférent leur siège régional à Kyiv, la capitale ukrainienne. Au minimum, cela montrera à Poutine et à ses bureaucrates-cleptomanes que l'Occident a une conscience. S'il vous plaît, agissez maintenant et transmettez ce message

Українці гинуть за права та свободу, які ми сприймаємо як належне. Хоча ніхто не очікує, що BP, Nestle та інші транснаціональні корпорації відмовляться від своїх відносин із Росією, бойкотуйте їх доки вони не переведуть свої регіональні штаб-квартири до Києва. Як мінімум, це надасть сигнал Путіну та його клептократам, що у Західа є совість. Дійте зараз та передайте це повідомлення далі

Menschen in der Ukraine sterben für die Rechte und die Freiheit, die wir für selbstverständlich halten. Obwohl niemand erwartet, dass BP, Nestle, P&G und andere multinationale Unternehmen sich weigern, von Ihren Beziehungen zu Russland, boykottíeren Sie die, bis Sie die regionale Zentrale nach Kiew verlegen. Zumindest es wird ein Signal sein an Putin und seine Kleptokraten, dass der Westen hat ein Gewissen. Handeln Sie jetzt und senden Sie diese Nachricht weiter

Gente di Ucraina muore per la sua indipendenza e liberta, questo è normale.Nessuno aspetta che BP, Nestle ed altri multinazionali smettono qualsiasi relazione con la Russia , baicotate loro, prima ,che ci trasferiscono le loro ufficci a Kiev.come il minimo,questo fara da segnale a Putin e suoi che l'ocidente a la coscienza pulita. Dovete aggire subito condividete questo messaggio

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)